Abstraction eliminates detail while precisely and accurately describing a system’s relevant behavior.

Because this notion of abstraction depends on choosing a filter, the same collection of events or observables are abstractable in different ways. Perhaps simultaneously: different abstractions can close over the same set behavior, while being equally accurate. Perhaps they contradict: different abstractions have the same output, but from mutually exclusive assumptions.

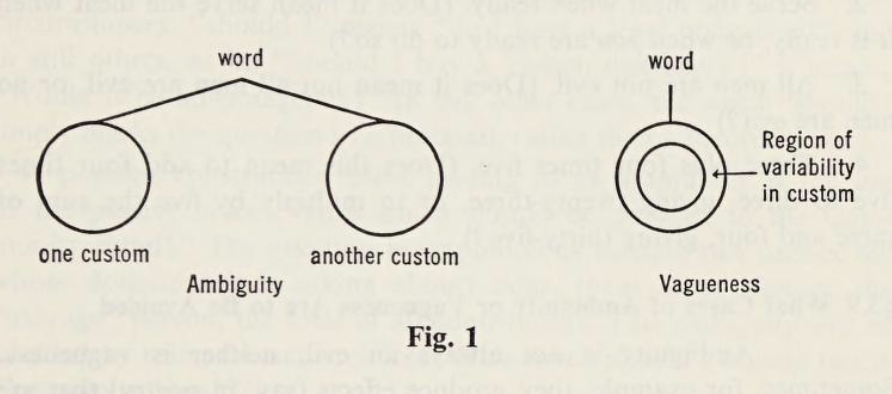

What distinguishes good abstractions from good definitions? It appears that everything said of abstraction can be said of definition. A good abstraction is not vague, and not ambiguous. Although abstraction is associated with sophistication, or can be used as a resource for verbal intimidation by intellectuals who work in generalities (I hear the irony!), the key role for abstraction is to simplify, without generality lost.

Vague definitions are general, while not having much to say. Rather, they say too little about too much. Abstraction is general, while containing multitudes of possibilities when combined with other abstractions, and when clarifying what matters within a tangled mess of system behaviors by excluding irrelevant specifics. Now we understand Dijkstra: “The purpose of abstracting is not to be vague, but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise.”

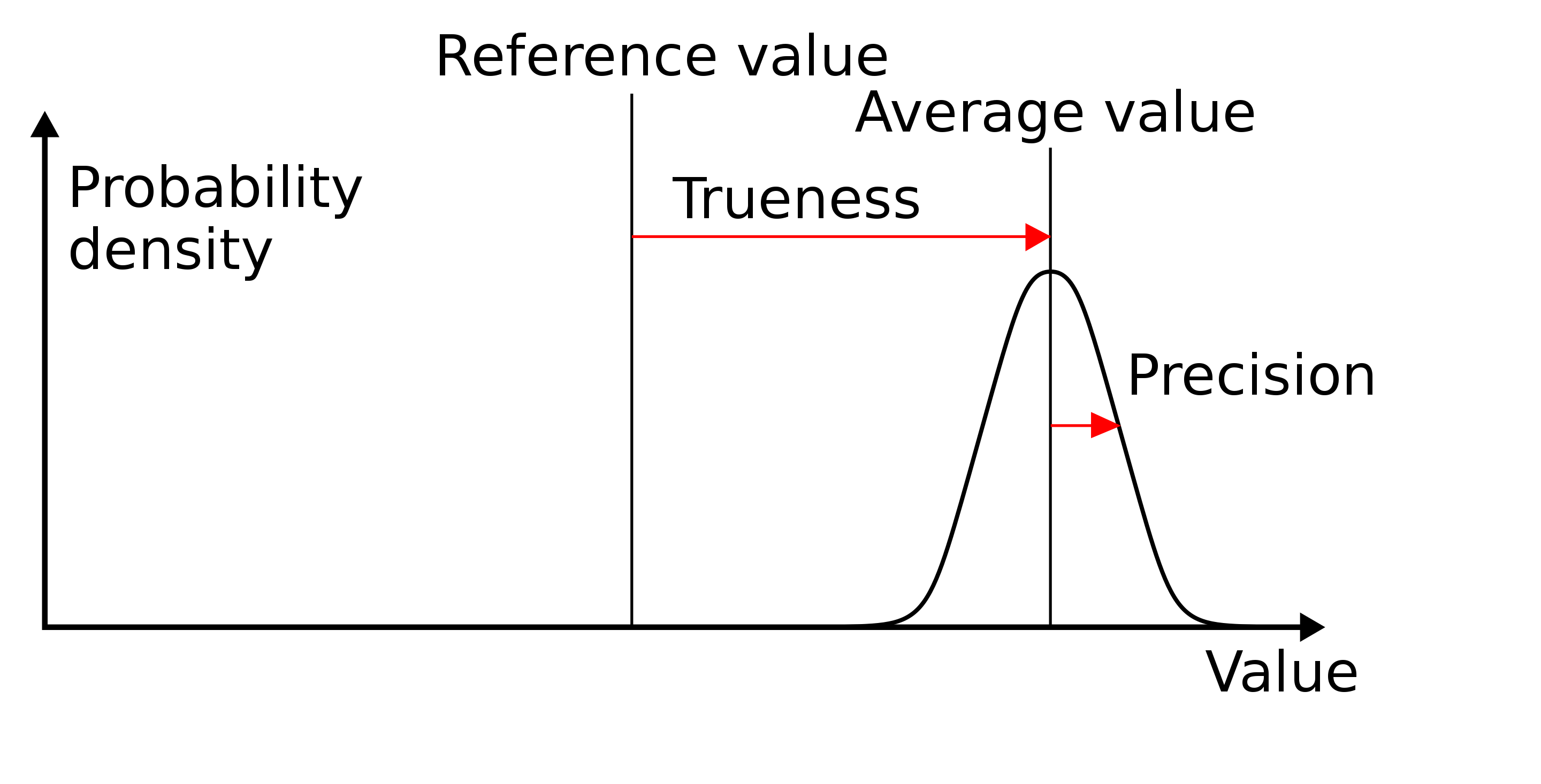

While precision must be maintained for an abstraction to be effective, and so increases when a definition becomes more dense, accuracy is normalized to “populations”, of otherwise unassociated examples of system behavior. Another decision must be made to restrict one’s observations that an abstraction “explains”, a constraint or boundary imposed as a reference to stop an abstraction from being wrong rather than being merely unclear, as well as making clarity easier to achieve by restricting how precise one needs to be to describe outlying cases.

The “detail” eliminated by abstraction is the number of parameters used to specify the majority of relevant behavior, if not all such behavior, of a system. What is missing, after ambiguity becomes accuracy and vagueness becomes precision, is one last distinction, woven into all written before this: compression.

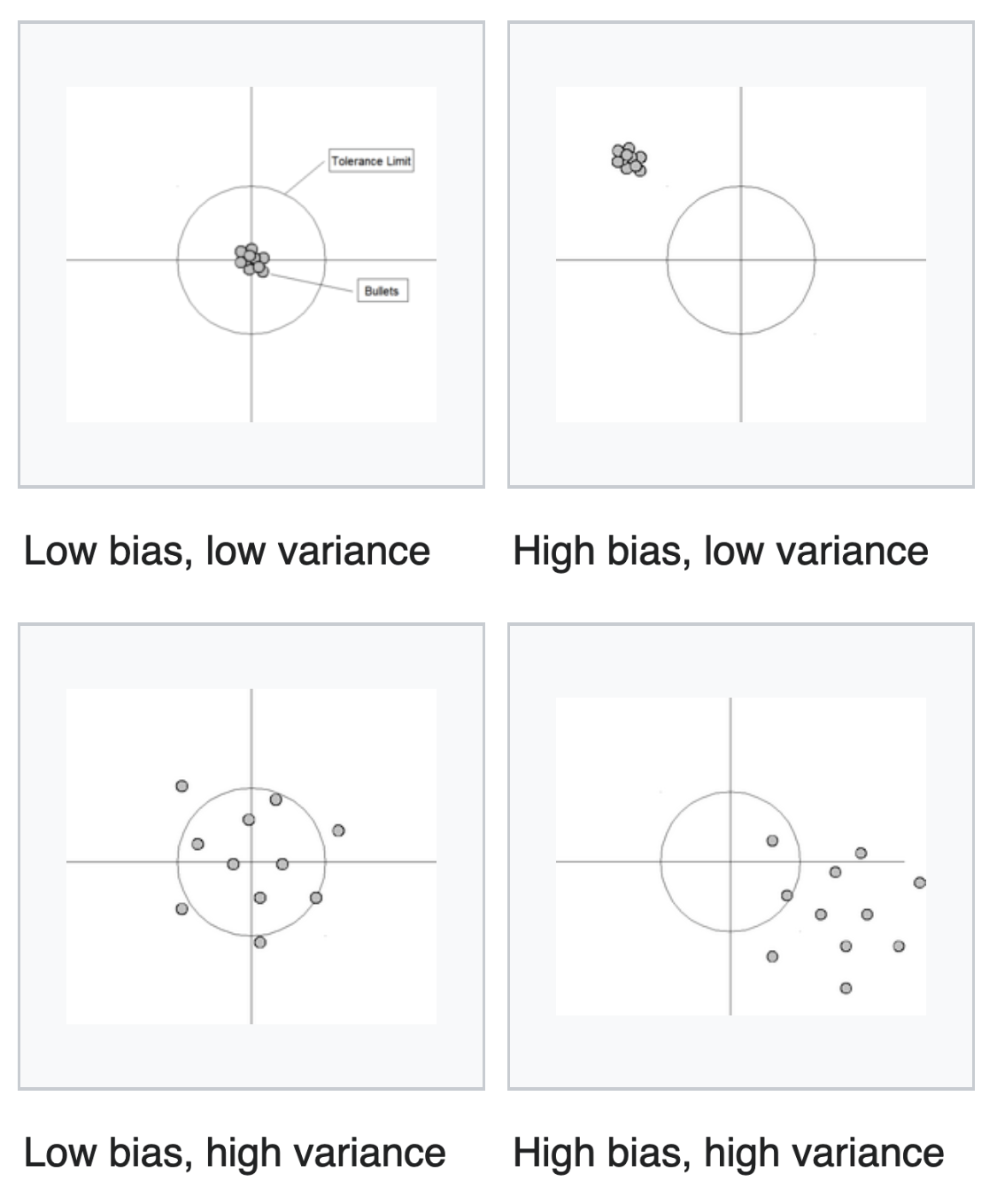

Accuracy-precision becomes bias-variance: drift from truth, tightness of claims. How often should one be right or wrong, and at what cost? The tradeoff claimed between bias and variance: do you enrich your abstraction by giving it more to explain, while risking being unable to define a meaningful central trend as you oversample a population?

For data scientists: define a model over a distribution of points describining observables with a cutoff of inclusion, to define errors and tune hyperparameters.

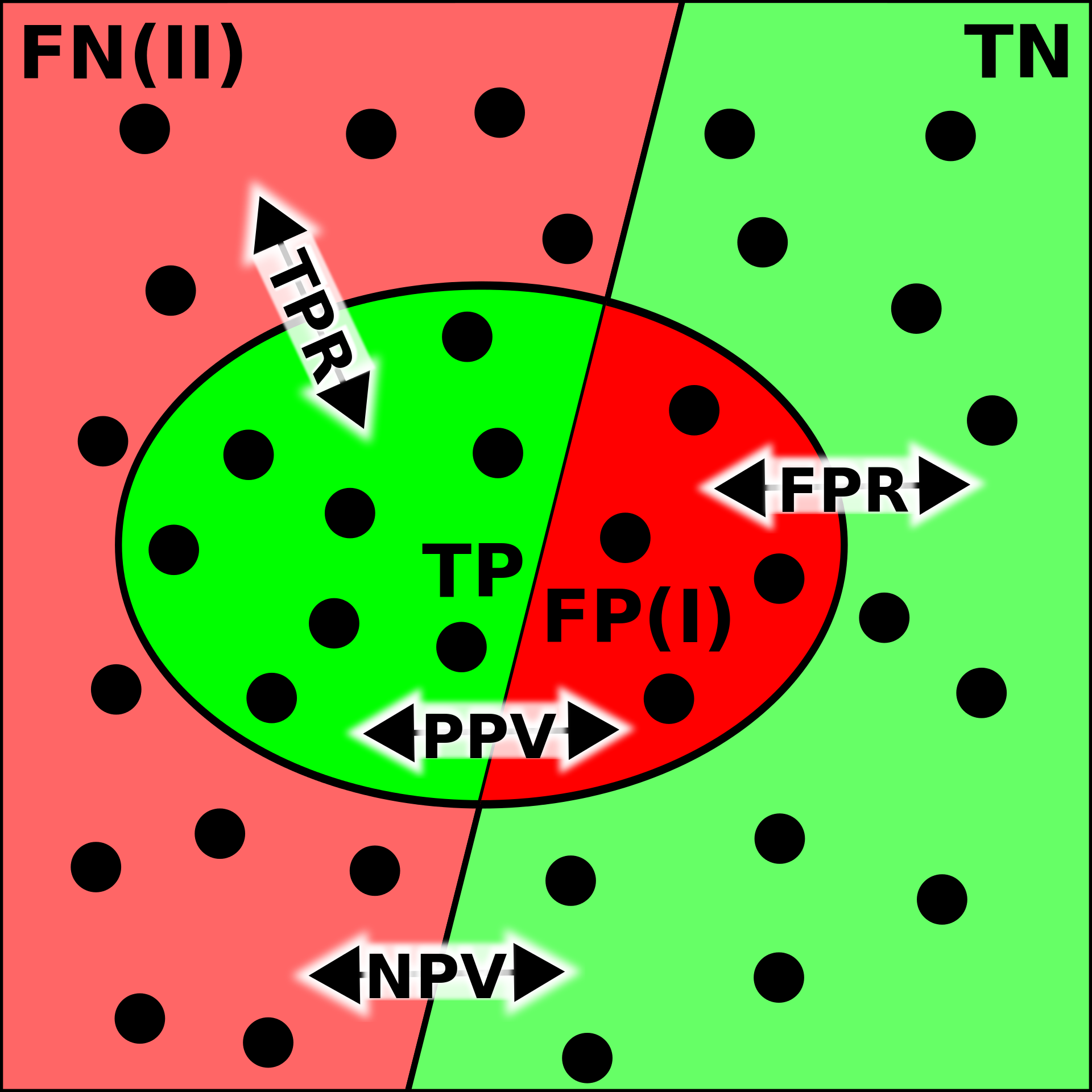

For computer scientists: construct a test oracle that shows when behavior is inside and outside of scope of an algorithm’s definition. Use this information to increase or reduce the number of cases your program can define via its arguments.

You can’t define more true positives for a model without increasing the false positive rate. You can’t define a cause when you don’t have a default state of affairs to compare against, excluding a possibility of difference without an intervention.

Here, “compression” is found in the number of parameters used to describe a system over the number of states it represents. In statistics it is a model’s goodness of fit: not too many parameters, not too few, as the model might define points outside of the distribution. In computer science it is an algorithm’s expressiveness. What is the minimum number of bits required to distinguish all of a system’s states? Is there a smaller program that produces all of those bits?

To detect the most compact set of invariants to describe a system by, and to define functionally what is even a part of that system, let alone what’s relevant in it: this task requires situational awareness. It no wonder there are so many approaches to defining compression and model control, yet accuracy and precision have canonical definitions in probability theory. Compression is not model dependent, it is domain dependent. How you look at the world constrains what symmetries you can perceive and exploit in your thinking. It is a hallmark of intelligence.

So, are all systems compressible? Whether a system’s observables are easily compressed depends on how much you want your abstraction to cover, your definition to close over, your theory to explain, your model to predict. Because it is a question of cost. Given infinite time you can imagine holding the world in your head, even though that is impossible - ask Maxwell and his demon.

We are part of that world: the day that a system’s model is equal to its existence is the day that we have found our god. Until then we should choose our abstractions wisely, effectively.

Resources:

- Constraints Liberate, Liberties Constrain (Youtube)

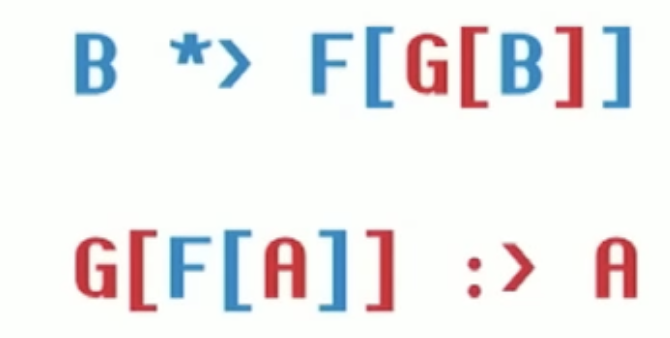

- A system’s expressivity is a relation between its lower and higher layers of representation. A good abstraction restricts possible states in favor only describing valuable states. This relation is a Galois Connection: a grouping of concretions should be as liberal as the tightest parameter set that describes the whole group. This ensures modularity = compositionality = well-defined boundaries.

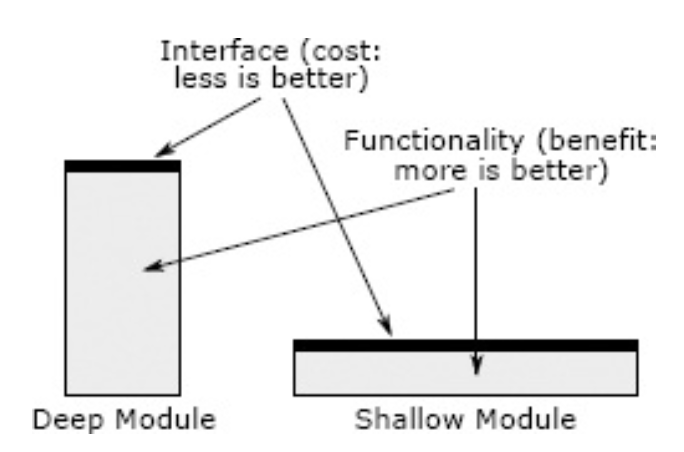

- A Philosophy of Software Design (Book)

- The ratio of a interface size to behavioral depth defines a quality abstraction.

- Lines and Curves (Book)

- Geometry is difficult because it is abstracting on pattern recognition in its rawest sense. One seeks to construct equivalences between figures and formulae: one that describes a point set, and the other that parameterizes that point set. A bidirectional relation between figure and formulae establishes a correct abstraction. But there is a non-symbolic component that requires sagacity.

- Seven Sketches in Compositionality (MIT)

- What does it mean for a system to be more than the sum of its parts? It defines a Galois Connection against its observers.

- Measuring Complexity (Nick Szabo)

- Logical complexity: how big of a program is required to produce all of the strings that distinguish the microstates of a system’s distribution of behavior?

- Entropy and Information: How much information is Needed to Assign a Probability? (Book Chapter)

- A meditation on the relationship between logical entropy and thermodynamic or statistical entropy. It’s technical, so the bottom line: you can do as much work as you need to to encode your priors, but after that, you will only learn as much as how exacting these priors were made.

- Duhem-Quine Thesis (Wikipedia)

- No scientific observation without theories and their assumptions. Defining relevance.

- Conditional Probability and Confusion Matrix (Towards Data Science)

- Derive the confusion matrix from conditional probability.

- Wikipedia